La lunga strada di sabbia, Lerici 17 Giu – Closed early

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia_017

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia

La lunga strada di sabbia

About This Project

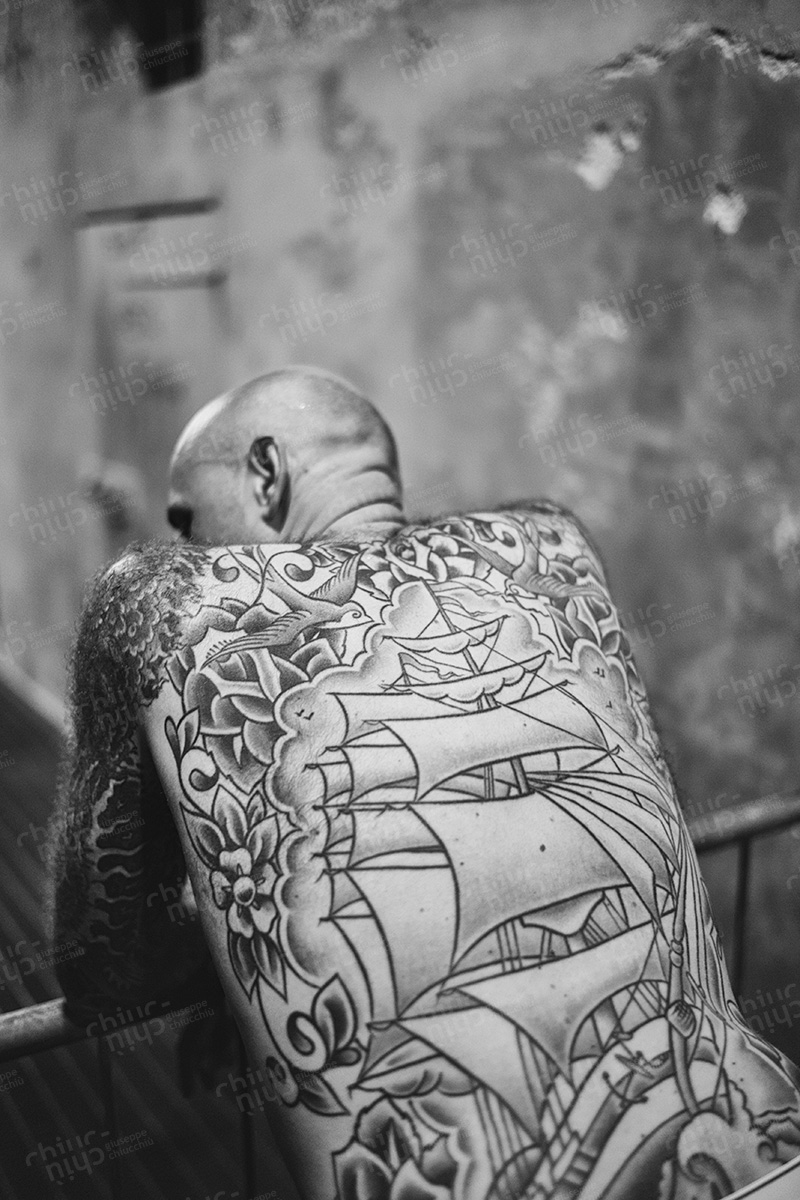

L’Italia ha insieme un’impronta europea e una mediterranea. La storia dei suoi settemila chilometri di costa è fatta di incontri e contaminazioni con popoli e civiltà che arrivarono per mare, greci, cretesi, fenici di Tiro e fenici di Cartagine. Quel mare i romani lo definirono “mare nostrum”. Più tardi fu in parte bizantino, in parte arabo ma quando iniziarono a solcarlo le galee delle Serenissime quel mare divenne o genovese, o pisano, o veneziano. Tutte le spiagge d’Italia, da quelle liguri a quelle flegree, dal golfo di Squillace al Gargano, dal Conero alla laguna di Grado sono mediterranee. Viaggiare lungo le coste è viaggiare nella storia di popoli diversi, entrare in una miriade di identità che si sono incrociate seguendo le rotte degli scambi e dei commerci innestandosi su una radice che le ha fatte proprie e le ha assimilate in una storia unica. Più Italie che recano su di sé, sulla linea del mare o nell’immediato entroterra, l’impronta di altrettanti popoli, una costa percorsa da dialetti diversi tanto da imbattersi, se ci si spinge all’interno, persino in comunità raccolte e rare in cui c’è chi parla occitano, o albanese, o sloveno, o greco. Se sui litorali della penisola e delle isole si incrociano cento Italie, ci sono anche cento modi per raccontarle. Nel 1959 Pier Paolo Pasolini visitò quei litorali a bordo di una “millecento Fiat” e descrisse in un celebre reportage quanto aveva visto su quella “lunga strada di sabbia”. Un racconto descrittivo tra scorci sconosciuti o emozionanti, tra italiani in vacanza, gente comune o personaggi mitici del Novecento, l’avvocato Agnelli, Fellini, Moravia; un racconto capace anche di restituire il profilo sociale del Paese alla vigilia del boom. Oggi che il miracolo economico è passato da più di mezzo secolo e le troppe cose che succedono ci fanno ripensare al boom come a un miraggio goduto per poco tempo, la “lunga strada di sabbia” regala le stesse emozioni a Giuseppe Chiucchiù, un giornalista che alla macchina per scrivere di Pasolini ha sostituito una macchina fotografica. L’intenzione è ancora quella di raccontare e il racconto coglie, lungo le coste, la ricchezza di quelle cento diverse identità e forse di altre ancora: marine italiane che evocano deserti africani, il blu dell’acqua incastonato fra muri rossi o arancioni che fa pensare ai contrasti cromatici di certe case nordiche affacciate sul mare. E’ un Maya oppure un marinaio scozzese del settecento l’uomo che piegandosi esibisce la nuda schiena coperta di tatuaggi? Sono aragonesi i due uomini e la bimba ritratti su un centro del litorale sardo, e forse l’immagine di quel prete che dialoga con due confratelli in cappa su un lungomare sconosciuto è un fotogramma colto in una lontana isola dell’Egeo? No, è Italia. Ogni risposta è verosimile eppure tutto questo è Italia, un’Italia dal tempo sospeso come quel nastro d’asfalto inanimato, senza macchine e senza uomini, o dal tempo cristallizzato come in quel tabernacolo agreste, fiori secchi e finti sul piccolo quadro della Vergine, o infine di un tempo perduto come quel passo di tango incastonato su un colonnato neoclassico: Italia o Argentina, oggi o primo decennio dell’Ottocento? Nella strada di sabbia italiana su cui si ferma l’obiettivo di Giuseppe Chiucchiù l’impronta di culture e popoli diversi si raccoglie in una intatta impronta mediterranea, “mare nostrum”, mai come ora spalancato su un mondo difficile.

Raoul Mancinelli, giornalista

“The hundred Italies of Giuseppe Chiucchiù”

Italy has both a European and Mediterranean imprint. The history of its seven thousand kilometers of coastline is marked by encounters and contaminations with peoples and civilizations that arrived by sea: Greeks, Cretans, Phoenicians from Tyre and Carthage. The Romans called that sea “mare nostrum.” Later it was partly Byzantine, partly Arab, but when the galleys of the Serenissime began to sail it, that sea became either Genoese, Pisan, or Venetian. All the beaches of Italy, from the Ligurian to the Phlegraean, from the Gulf of Squillace to the Gargano, from Conero to the lagoon of Grado, are Mediterranean. Traveling along the coasts is traveling through the history of different peoples, entering into a myriad of identities that have crossed paths following the routes of trade and commerce, and grafting themselves onto a root that made them their own and assimilated them into a unique history. There are more than one Italy that bear on themselves, on the coastline or in the immediate hinterland, the imprint of just as many peoples, a coast traversed by different dialects so much so that, if you venture inland, you may even come across gathered and rare communities in which some speak Occitan, Albanian, Slovenian, or Greek. If a hundred Italies intersect on the coasts of the peninsula and islands, there are also a hundred ways to tell them. In 1959, Pier Paolo Pasolini visited those coasts aboard a “millecento Fiat” and described in a famous reportage what he had seen on that “long sandy road.” A descriptive story among unknown or exciting glimpses, among Italians on vacation, ordinary people, or mythical figures of the twentieth century, lawyer Agnelli, Fellini, Moravia; a story also capable of restoring the social profile of the country on the eve of the economic boom. Today, more than half a century after the economic miracle has passed, and too many things that happen make us rethink the boom as a mirage enjoyed for a short time, the “long sandy road” still gives the same emotions to Giuseppe Chiucchiù, a journalist who has replaced Pasolini’s typewriter with a camera. The intention is still to tell, and the story captures, along the coasts, the richness of those hundred different identities and perhaps others as well: Italian seascapes that evoke African deserts, the blue of the water set between red or orange walls that brings to mind the chromatic contrasts of certain northern houses overlooking the sea. Is the man bending over to show his bare back covered in tattoos a Mayan or an eighteenth-century Scottish sailor? Are the two men and the girl portrayed on a beach in Sardinia Aragonese, and perhaps the image of that priest who dialogues with two brothers in capes on an unknown promenade is a frame captured on a distant Aegean island? No, it’s Italy. Each answer is plausible, and yet all of this is Italy, an Italy suspended in time like that lifeless strip of asphalt, without cars and without men, or crystallized in time like that rural tabernacle, dry and fake flowers on the small picture of the Virgin, or finally lost in time like that tango step set on a neoclassical colonnade: Italy or Argentina, today or the first decade of the nineteenth century? On the Italian sandy road where Giuseppe Chiucchiù’s lens stops, the imprint of different cultures and peoples gathers in an intact Mediterranean imprint, “mare nostrum,” now more than ever open to a difficult world.

Quali sono le prospettive con cui possiamo avvicinarci alla scoperta di Lerici? Lerici è sicuramente un borgo ligure, tipicamente italiano, costiero, mediterraneo. Sì, solo un piccolo puntino sulla carta geografica, connesso però da questo grande mare nostrum a un’infinità di altri puntini costieri non solo italiani, ma francesi, spagnoli, greci, slavi, nordafricani. Il mare fa dei popoli un’unica razza: la gente di mare. In questa prospettiva Lerici è quindi parte di un insieme, maglia di una rete. Ma c’è anche una seconda prospettiva, quella capovolta, quella in cui Lerici non è parte di un insieme ma un unicum, una realtà con la sua identità ben definita e lontana da qualsiasi altra. Lerici è il Golfo dei Poeti. È quel luogo dove da centinaia di anni i maggiori poeti e scrittori e artisti, prima o poi passano, vivono, muoiono. Lerici ha un genius loci, ha quel qualcosa che non si può spiegare a parole ma che in effetti esiste, che attrae, rapisce le personalità dotate di una sensibilità straordinaria, come quella di molti scrittori, pittori, attori. Quando dall’entroterra si apre la visuale a Bellavista e l’azzurro e la luce invadono gli occhi, o quando scendendo da San Terenzo, in mezzo alle case, nelle vie strette, ad un certo punto eccolo lì, il mare. I panorami del nostro golfo lasciano senza fiato chiunque. Posso solo immaginare come si sia potuto sentire chi, con la sensibilità e l’animo predisposto alla bellezza, sia arrivato qui la prima volta. Uno sconquasso emotivo, un turbine di impressioni che poi si sono tradotte nei versi di Percy Bysshe Shelley, nelle descrizioni di Virginia Wolf, nei racconti di Pier Paolo Pasolini. È facile vivendo qui sentirsi abbracciati dalle insenature, accolti dalle spume del mare e dall’armonia delle colline, quasi a formare un guscio, un nido. Ma è altrettanto facile incontrare persone delle nazionalità più lontane, sentir parlare ogni lingua conosciuta, e conoscere. Conoscere l’unico e il diverso. “La lunga strada di sabbia” che Pasolini tracciò nel 1959 passa anche da qui, unendo il nostro puntino, all’infinità.

Leonardo Paoletti, sindaco di Lerici

What are the perspectives with which we can approach the discovery of Lerici? Lerici is certainly a Ligurian village, typically Italian, longshore, Mediterranean. Yes, just a small dot on the map, connected by this great mare nostrum to an infinity of other longshore dots, not only Italian, but French, Spanish, Greek, Slavic, North African. The sea makes a single race of peoples: sailors. In this perspective, Lerici is therefore part of a whole, a mesh of a network. But there is also a second perspective, the opposite one, the one in which Lerici is not part of a whole but a unicum, a reality with its own well-defined identity and far from any other. Lerici is the Gulf of Poets. It is that place where for hundreds of years the greatest poets and writers and artists, sooner or later pass, live or die. Lerici has a genius loci, something that cannot be explained in words but which actually exists, which attracts, runs over personalities with an extraordinary sensitivity, as are many writers, painters and actors. When, from the hinterland the view opens up to Bellavista and the blue and the light invade your eyes, or when coming down from San Terenzo, among the houses, in the narrow streets, at a certain point here it is, the sea; the panoramas of our gulf leave anyone breathless; I can only imagine how someone with sensitivity and a soul open to beauty could have felt, arriving here for the first time. An emotional tumult, a whirlwind of impressions which then translated into the verses of Percy Bysshe Shelley, into the descriptions of Virginia Wolf or into the stories of Pier Paolo Pasolini. Living here, it is easy to feel embraced by the coves, welcomed by the foam of the sea and by the harmony of the hills, almost forming a shell, a nest. But, at the same time it is easy to meet people of the most far nationalities, hear every known language spoken, and know. Know the unique and the different. “The long sandy road” that Pasolini traced in 1959 also passes through here, joining our dot to an infinity.

Leonardo Paoletti, mayor of Lerici

Giuseppe Chiucchiù’s life journey unfolds as a compelling narrative, woven with experiences and adventures that span the diverse landscapes of the world. Born in Latina and artistically shaped in Germany, he embarked on the path of his photographic career with a passion that guided him through complex and fascinating contexts.

His career as a freelance photojournalist began in 1988 with the Ansa Agency, leading to collaborations with prestigious editorial groups such as L’Espresso, Rizzoli, Rusconi, and Mondadori until 2009. His keen eye and ability to capture significant moments allowed him to establish himself as one of the most talented professionals in his field.

Among the milestones of his career, stand out the reports made in El Salvador in 1989 during the Farabundo Martì Front war, his coverage of the Romanian revolution in 1990 that led to Ceausescu’s fall, and his commitment to the phenomenon of Nazi-skin in Germany in 1991. In 1992, Chiucchiù found himself in the war theaters of Bosnia and Herzegovina, documenting the horrors of Mostar and Sarajevo, and later following Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign in the United States.

His career has been marked by exclusive scoops, such as the photo service on Lucio Battisti after his withdrawal from the scene, which garnered significant media interest. In 1993, his in-depth reportage on Orthodox Jewish communities in the state of New York earned him the prestigious “Nikon Photo International” award.

In the following years, Chiucchiù continued to explore the world through his lens, capturing the Zapatista rebellion in Chiapas, Mexico, developments in Israel after the attack on Isaac Rabin, coal mines in the southwestern region of China, and the extraordinary gathering of the Kumb Mela in India, with millions of Hindus gathered on the banks of the Ganges.

The recognition of the “Premio Senigallia – Io Fotoreporter” in 2018 marked a significant milestone in his career, emphasizing the value and importance of his contribution to the art of photography. Another key moment in his professional life was associated with his participation in the Art.Fair Messe für moderne und aktuelle Kunst in Cologne, Germany, in 2016. During this event, Chiucchiù had the opportunity to exhibit and share his work with an international audience, further solidifying his reputation in the world of photography. This pivotal moment represented a precious occasion to showcase his innovative and engaging work to a broad audience, underscoring his presence in the artistic and photographic landscape. The Art.Fair Messe für moderne und aktuelle Kunst in Cologne in 2016 provided Chiucchiù with a platform to display his unique perspective and talent, contributing to cementing his prominent position in the contemporary photographic scene.

His bibliography is enriched by two significant photographic volumes, “Marche terra sconosciuta” and “Le colline del sogno,” offering a deep and sensitive look at the places he has traversed.

The life and work of Giuseppe Chiucchiù are a captivating narrative of dedication, passion, and a continuous pursuit of beauty and truth in the world around him.

Il percorso di vita di Giuseppe Chiucchiù si sviluppa come un avvincente racconto narrativo, intessuto di esperienze e avventure che spaziano attraverso i panorami più vari del mondo. Nato a Latina e plasmato artisticamente in Germania, ha intrapreso il cammino della sua carriera fotografica con una passione che lo ha guidato attraverso contesti complessi e affascinanti.

La sua carriera da fotoreporter freelance ha avuto inizio nel 1988 con l’Agenzia Ansa, aprendo le porte a una serie di collaborazioni con prestigiosi gruppi editoriali come L’Espresso, Rizzoli, Rusconi e Mondadori fino al 2009. Il suo sguardo acuto e la sua abilità nell’immortalare momenti significativi gli hanno consentito di affermarsi come uno dei professionisti più talentuosi nel suo campo.

Tra le pietre miliari della sua carriera, emergono i reportage realizzati in Salvador nel 1989 durante la guerra del Fronte Farabundo Martì, la sua copertura della rivoluzione rumena del 1990 che portò alla caduta di Ceausescu, e il suo impegno nei confronti del fenomeno dei nazi-skin in Germania nel 1991. Nel 1992, Chiucchiù si è trovato nei teatri di guerra della Bosnia Erzegovina, documentando gli orrori di Mostar e Sarajevo, per poi seguire la campagna presidenziale di Bill Clinton negli Stati Uniti.

La sua carriera è stata contrassegnata da scoop esclusivi, come il servizio fotografico su Lucio Battisti dopo il suo ritiro dalle scene, che ha suscitato un notevole interesse mediatico. Nel 1993, il suo approfondito reportage sulle comunità di Ebrei ortodossi nello Stato di New York gli ha meritato il prestigioso premio “Nikon Photo International”.

Negli anni successivi, Chiucchiù ha continuato a esplorare il mondo attraverso il suo obiettivo, catturando la ribellione zapatista del Chiapas in Messico, gli sviluppi in Israele dopo l’attentato a Isaak Rabin, le miniere di carbone nella regione sud-occidentale della Cina, e il raduno straordinario del Kumb Mela in India, con milioni di Hindu riuniti sulle rive del Gange.

Il riconoscimento del “Premio Senigallia – Io Fotoreporter” nel 2018 è stata una tappa significativa nella sua carriera, sottolineando il valore e l’importanza del suo contributo all’arte della fotografia. Un altro momento chiave nella sua vita professionale è stato legato alla partecipazione alla Art.Fair Messe für moderne und aktuelle Kunst di Colonia in Germania nel 2016. Durante questo evento, Chiucchiù ha avuto l’opportunità di esporre e condividere la sua opera con un pubblico internazionale, consolidando ulteriormente la sua reputazione nel mondo della fotografia. Questo momento chiave ha rappresentato un’occasione preziosa per presentare il suo lavoro innovativo e coinvolgente a un vasto pubblico, sottolineando la sua presenza nel panorama artistico e fotografico. La Art.Fair Messe für moderne und aktuelle Kunst di Colonia del 2016 ha fornito a Chiucchiù uno spazio per mettere in mostra la sua prospettiva unica e il suo talento, contribuendo a consolidare la sua posizione di rilievo nella scena fotografica contemporanea.

La sua bibliografia è arricchita da due volumi fotografici importanti, “Marche terra sconosciuta” e “Le colline del sogno”, che offrono uno sguardo profondo e sensibile sui luoghi che ha attraversato.

La vita e il lavoro di Giuseppe Chiucchiù sono un racconto avvincente di impegno, passione e una continua ricerca della bellezza e della verità nel mondo che lo circonda.